Machine Learning (ML) has numerous applications in medicine, including disease diagnosis, drug development, predictive healthcare, and more. One key application of ML in medicine is biomedical image processing. These types of models takes an image as an input and then assigns a class label to each pixel in a process called localisation. Competitions are held annually to advance these ML models for biomedical image processing tasks. For instance, the International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) hosts yearly competitions focused on various biomedical imaging challenges. One notable problems from the ISBI involves segmenting neuronal structures in electron microscopy stacks.

In 2012, the winner of this competition employed a sliding-window approach. This method involved using a window to assign each pixel a class based on the information within a patch of the image. The approach had two main advantages. First, it enabled the model to localize effectively. Second, it required less training data because multiple patches could be generated from each image.

However, there were two major disadvantages. Firstly, the network was slow because each image patch had to be processed individually. Secondly, there was a tradeoff between localization accuracy and the use of context. Using a larger patch size provided more context but to manage the increased image size, max-pooling had to be applied for efficiency, which reduced localization accuracy. Conversely, using a smaller patch size provided less context, which also diminished accuracy.

U-Net provides an alternative approach with a distinctive architecture consisting of two paths: the contracting path and the expansive path, often referred to as the encoder path and decoder path in later papers. The contracting path extracts features from the original image using convolution layers followed by pooling to downsample, effectively reducing the spatial dimensions and capturing the context.

The expansive path, or decoder path, focuses on reconstructing the image segmentation from the abstract features obtained in the contracting path. This is achieved through the use of upsampling, which progressively restore the spatial dimensions. This upsampling process allows the decoder to recover fine details and achieve precise localization, resulting in accurate segmentation.

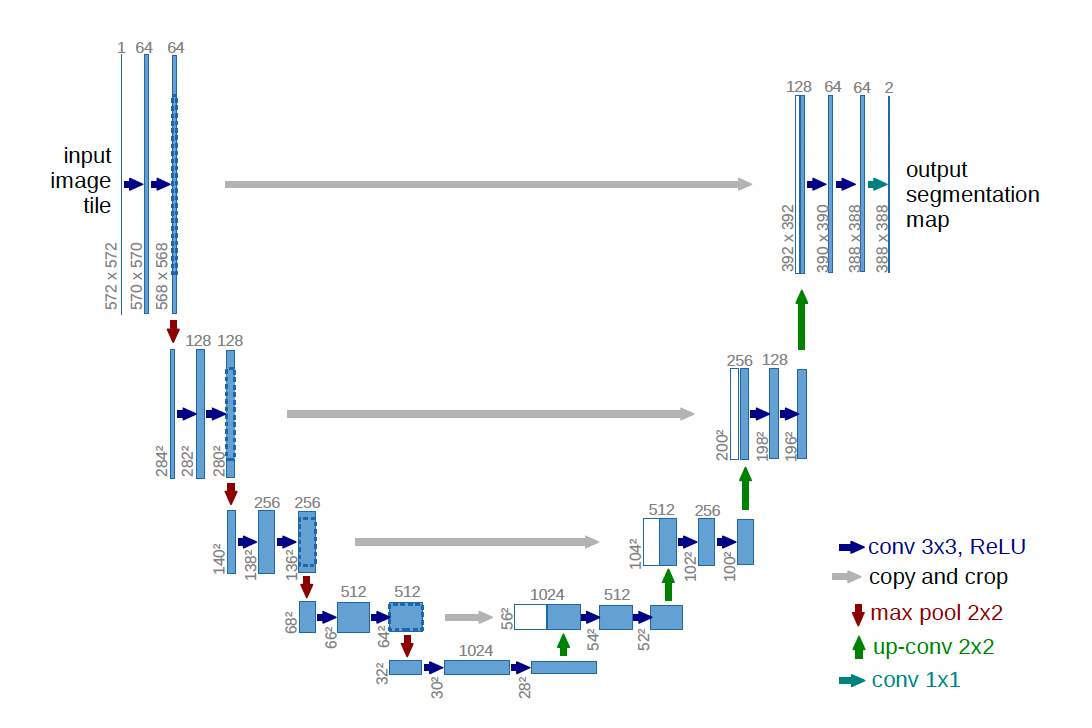

Figure 1: U-Net Architecture. Source: Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. and Brox, T. (n.d.). U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1505.04597

In the pooling process, the encoder loses a significant amount of fine-grained information. To help the decoder achieve precise localization, skip connections are added between the encoder and decoder layers. These skip connections concatenate the encoder’s layers with the corresponding decoder layers, helping the decoder preserve finer details. Skip connections provide direct pathways to previous layers in the network, which helps maintain the gradient of the parameters and prevents them from vanishing.

The U-Net architecture is illustrated in Figure 1. The contracting path is on the left, and the expansive path is on the right. The contracting path closely resembles convolutional networks, with repeated 3x3 convolutions followed by rectified linear units (ReLU). Downsampling is achieved using a 2x2 max pooling layer with a stride of 2, and the number of filters doubles at each downsampling step.

The expansive path performs the opposite operations. It uses 2x2 up-convolutions to upsample the image, reducing the number of feature maps accordingly. Following the upsampling, 3x3 convolutions are applied, each followed by a ReLU. Finally, 1x1 convolutions are used to map the final feature maps to the desired number of output classes.

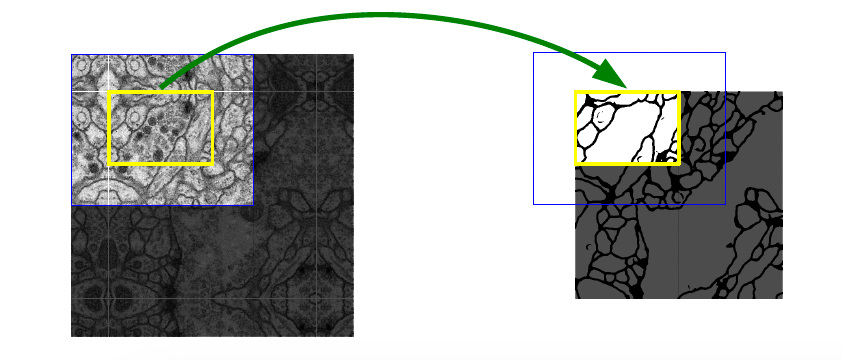

The input to the U-Net is a patch of the original image. To provide context for each patch, an overlap-tile strategy is used (figure 2). In this strategy, the centre of the patch is the area of interest for prediction, while the surrounding region provides context for the central section. Every patch inputs into the model overlaps with adjacent patches, ensuring continuous context and accurate predictions.

Figure 2: Overlapping boundary boxes. Source: Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. and Brox, T. (n.d.). U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1505.04597

In the case the middle section (the area bounded by the yellow box) is on the boundary of the original image a mirroring operation is performed to create context around the boundary.

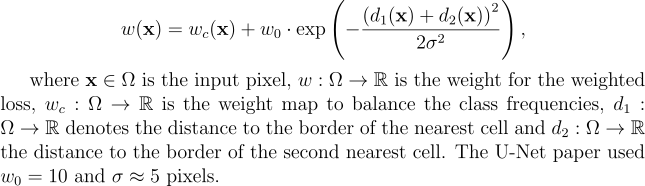

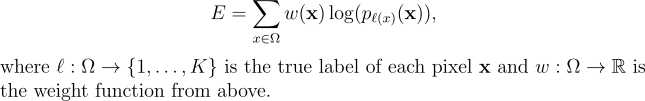

Another challenge the U-net authors encountered was the separation of touching objects of the same class. A weighted loss was introduced to address this issue. This weighted loss adds more weight to pixels to the boundary of two different classes. The weight function is written as

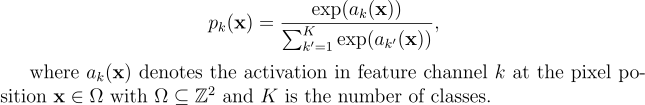

This weight function is applied to the energy function. The energy function is a combination of the pixel-wise softmax function and the cross entropy loss function.

The softmax function takes the form below:

The energy function takes the form below:

Since its introduction, the U-Net architecture has set new benchmarks in biomedical segmentation tasks, notably excelling in the ISBI challenge for segmenting neuronal structures in electron microscopy stacks. U-Net continues to demonstrate high performance, and its influence is evident in many contemporary machine learning models for biomedical image segmentation. Modern architectures often draw heavily from U-Net’s design principles, showcasing its lasting impact and relevance in the field.

References:

For further details on the training and the experimental results of the U-Net model I’d highly encourage reading the paper by Olaf Ronneberger about U-Net.

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. and Brox, T. (n.d.). U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1505.04597.