Summary

Graphs are incredibly useful for modelling a range of relationships and interactions. Using nodes to represent entities and edges to represent connections between these entities, they have become a very useful representation tool. Nowadays they are used to model social networks, protein-protein interactions, recommendations systems, knowledge graphs, supply chains, and so much more. However, as these graphs scale up and add more nodes and edges, a range of issues start to arise. They start to become computationally expensive to process, noisy, and difficult to interpret.

To overcome some of these issues, embedding algorithms were invented. In essence, these algorithms reduce the graph data to a lower dimension while also creating a rich lower dimensional representation by incorporating structural and semantic information in the form of a vector. These methods are scalable to massive graphs and are compatible with standard machine learning models.

Today’s article will look into these embeddings methods. We’ll first start by briefly covering the graph embedding problem and the role that encoder-decoder models play it this setting. Next, we will quickly glance over the difference between shallow and deep embeddings methods before delving deeply into the graph factorisation shallow embedding methods. Some of the graph factorisation methods we will be covering include Laplacian Eigenmaps, Graph Factorisation, GraRep, and more. The other group of shallow embedding methods, namely the random walk methods will be covered in a later article.

This article should serve as an introduction into some of the shallow graph embedding techniques. I’d highly recommend reading the papers attached in the references section. There they delve into these methods at a much greater detail then we will be diving into today.

What are Node Embeddings?

Let’s start with the basics. What are node embeddings? In short, they are a lower dimensional representation of the node’s position and the structure of their local graph. The process of mapping these nodes to this lower dimension is often referred to as encoding nodes.

These node embedding strategies fall into 2 groups: shallow embeddings and deep embeddings.

Shallow embedding methods focus on learning low-dimensional embeddings without using complex mechanisms. As a result, shallow embedding methods are often simpler and more scalable than the deep learning-based methods. Shallow embedding methods focus on node proximity, first-order proximity, second-order proximity, and edge weights (for weighted graphs). But they lack the complexity requires to capture complex patterns. Some of the disregarded pieces of information include node features, edge features, edge types, graph global structure, and higher-order relationships.

The basic strategy around these methods involve factoring the adjacency matrix or some variant of the adjacency matrix. The factored matrices are then mapped to a lower dimensional representation. Some of the well known shallow embedding methods include DeepWalk, LINE, and node2vec.

Deep embedding methods use neural network to learn graph representations. These methods are more expressive and are able to learn rich embeddings from incorporating graph information and structure. Methods which fall into this category are called Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). Example GNNs include Graph Convolution Networks, GraphSAGE, Graph Attention Networks (GAT), and Variational Graph Autoencoders (VGAE). These methods will not be covered today but will be covered in a later article.

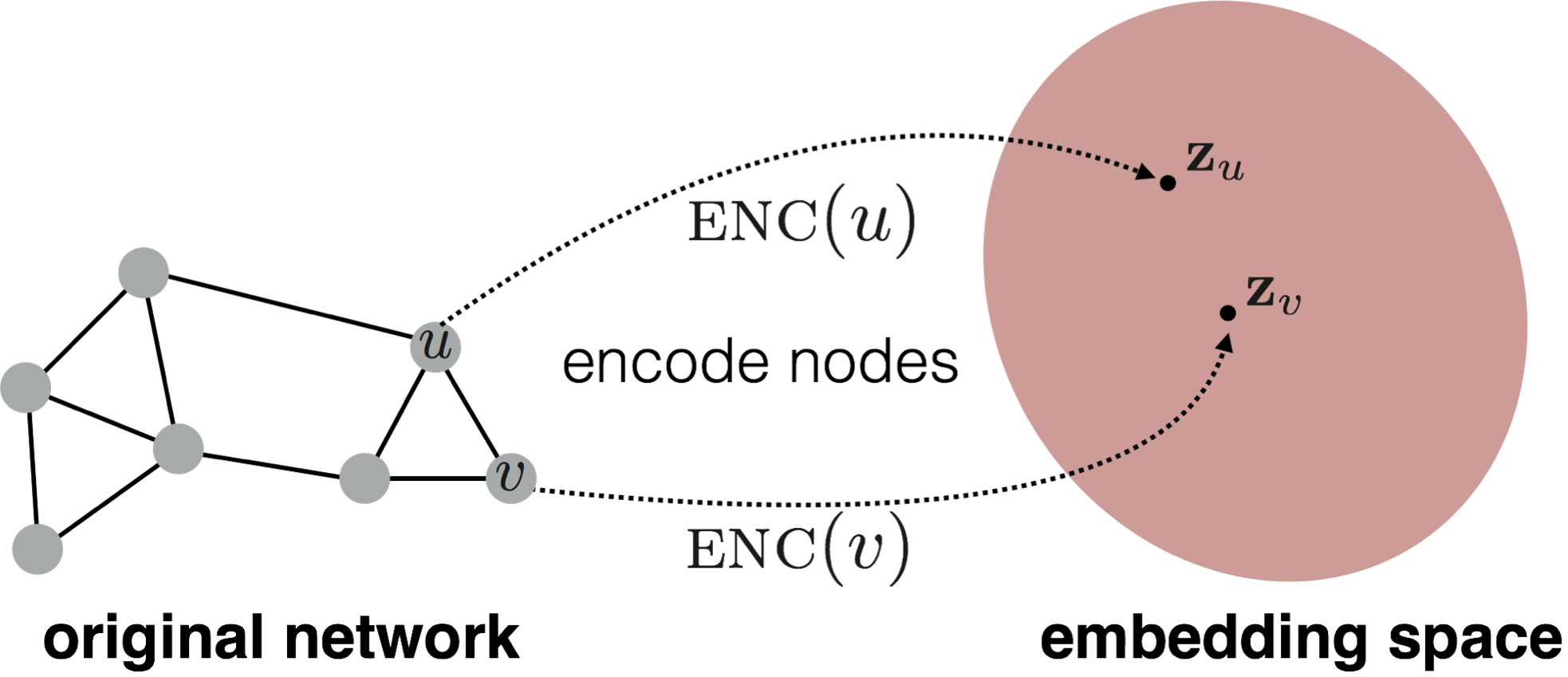

To create these lower-dimensional embeddings, an encoder-decoder framework is needed. The encoder takes the graphs node and maps the nodes to a the latent space as a lower dimensional vector. The decoder does the opposite, it takes the lower-dimensional vector from the latent space and maps it back to its higher dimensional vector.

Encoder

Given nodes in vector space $ v \in \mathcal{V}$ and an encoder $\text{ENC}:\mathbb{R}^{n} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{d}$, where $d < n$, the encoder maps these vectors $v$ to a lower dimensional space $\text{ENC}(v) = \bm{z}_{v}$.

Figure 1. Example encoder creating node embeddings. Source: William, W.L. (2022). Graph Representation Learning. Springer Nature.

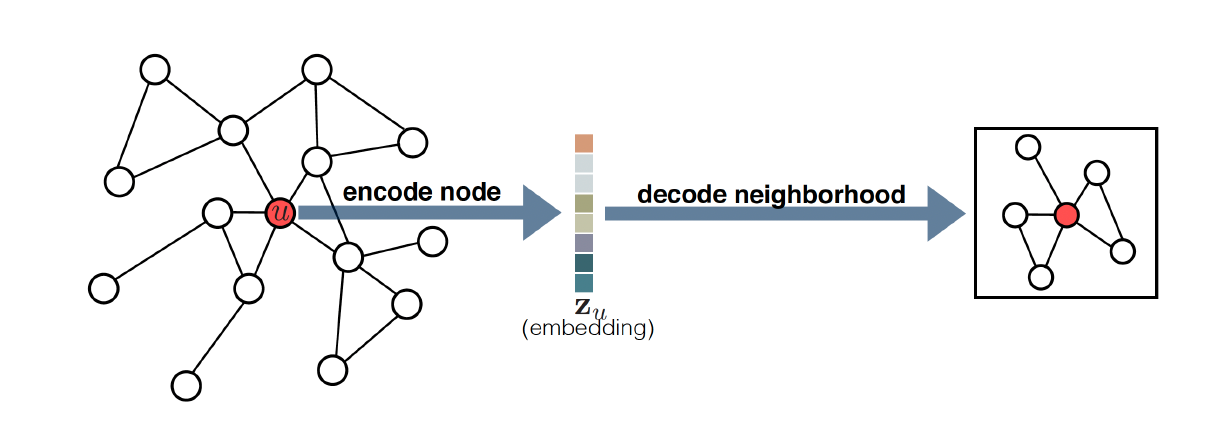

Decoder

The decoder goal is opposite to the encoder. It tries to reconstruct the node and graph properties from the node embeddings. For example, the decoder $DEC$ may try to determine the vector $v$’s neighbour given the embedded vector $\bm{z}_{v}$.

In practice, the decoders are used to determine the similarity between two pairs of nodes. More specifically, given two lower dimensional vectors $\bm{z}_{u}$ and $\bm{z}_{v}$, we say the decoder is trying to reconstruct the relationship between nodes $u$ and$v$.

Figure 2. An example encoder-decoder procedure. Source: William, W.L. (2022). Graph Representation Learning. Springer Nature.

The general goal of encoder-decoder based shallow embedding methods is to minimise the encoder and decoder reconstruction loss. In other words, minimise the difference between the original data $\bm{S}$ and reconstructed data. Mathematically, this is written as:

$$\text{DEC}(\text{ENC}(u), \text{ENC}(v)) = \text{DEC}(\bm{z}_u, \bm{z}_v) \approx \bm{S}[u, v], $$where $\bm{S}[u, v]$ is the graph-based similarity measure between nodes and tells us how nodes are connected. There are many different definitions for the similarity matrix based on which algorithm is applied. Common similarity matrices include the adjacency matrix, laplacian matrix, and the node transition probability matrix. For the rest of this paper we will use the matrix $\bm{S}$ to denote the similarity matrix.

In the problem of finding whether nodes are neighbours, the similarity measure would correspond to the adjacency matrix $\bm{A}$, i.e. $\bm{S}[u, v] \stackrel{\triangle}{=} \bm{A}$.

Note that the symbol $\stackrel{\triangle}{=} $ should be read as “defined as”.

Optimisation

To optimise our encoder-decoder model we need to minimise the empirical reconstruction loss over all the set of node pairs $\mathcal{D}$. In other words, we need to minimise the error between the original data and its reconstruction.

$$\mathcal{L} = \sum_{(u, v) \in \mathcal{D}} \ell (\text{DEC}(\bm{z}_{u}, \bm{z}_{v}), \bm{S}[u, v]),$$where $\ell$ denotes the loss function. Common loss functions include the mean square error and the cross entropy loss.

Now that we have set the problem, the next step is to choose the decoder, similarity measure, and loss function. There are 2 groups of methods to choose from: factorisation based approaches and random walk embeddings. Today we will be focusing on the factorisation based approaches.

Factorisation Based Approaches

Some of the earliest graph based embedding methods were based on using factorisation to approximate a pair of node’s similarity. Here, a factorisation of the similarity matrix can be used to encode the data to a lower dimension. These factorisation methods include:

- Singular Value Decomposition (SVD).

- Non-Negative Matrix Factorisation (NMF).

- Alternating Least Squares (ALS).

Within the factorisation based approaches, we’ll look into 4 methods: Locally Linear Embeddings (LLE), Laplacian Eigenmaps, Graph Factorisation, and GraRep.

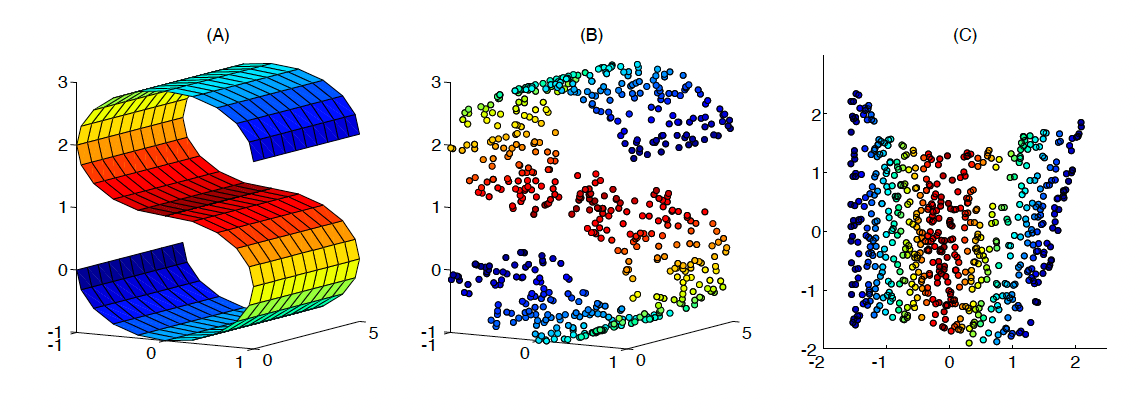

Locally Linear Embedding

The oldest of these methods is the Locally Linear Embeddings (LLE). This non-linear dimensionality reduction technique assumes each node lies near a smooth non-linear manifold of lower dimension. Consequently, there exists a translation, rotation, or rescaling method that maps the high dimensional data to the lower dimension manifold’s neighbourhood.

Figure 3. An example of LLE mapping a three dimensional space to a 2 dimensional space. Source: Roweis, S.T. (2000). Nonlinear Dimensionality Reduction by Locally Linear Embedding. Science, 290(5500), pp.2323–2326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5500.2323.

LLE starts by acquiring the k nearest neighbours for each node. With the node’s neighbours found, weights are then assigned to these neighbouring nodes that best reconstruct each node from its neighbours in the high dimensional space. Specifically, for node $x_{i}$, the goal is to find the weights $w_{ij}$ such that $x_{i} \approx \sum_{j \in \mathcal{N}_{i}} w_{ij} x_{j}$, where $\mathcal{N}_{i}$ denotes the neighbourhood for node $x_{i}$ . This problem is referred to as finding the weights which minimise the reconstruction error.

$$\argmin_{w}\sum_{i}\|x_{i} - \sum_{j} w_{ij} x_{j}\|^{2}$$, under the constraints that $\sum_{j} w_{ij} = 1$.

Minimising the reconstruction error for all data points gives weight matrix $W \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n}$, where $n$ denotes the number of nodes. This weight matrix is next used to create the Laplacian matrix by $L = (I-W)^{T}(I-W)$ where $I$ is the identity matrix. More details about Laplacian matrices can be found in the appendix.

Now that we have found our Laplacian $L$, the next step is to find the eigenvectors of our Laplacian $L$ with the corresponding d smallest non-zero eigenvalues. Solving this eigenvalue problem gives us the smallest eigenvectors to map the data points to a lower dimensional space, i.e. $L$ is approximated by $L_{d}$ where the columns of $L_{d}$ are the eigenvectors with the first d non-zero eigenvalues.

In most dimensional reduction algorithms, the algorithms tend to search for the largest eigenvalues, however in LLE they search for the d smallest non-zero eigenvalues. This is a consequence of the Rayleitz-Ritz theorem where the smallest eigenvalues correspond to smooth variations across the graph. This assumption implies that the connected nodes will have similar eigenvectors.

This is very different from the PCA method which captures the largest eigenvalues. PCA aims to reduce the dimensionality of the data by capturing the most variance. To do this PCA finds the largest eigenvalues as they correspond to the greatest variance. This is different to LLE which focuses on preserving smoothness in the data.

Laplacian Eigenmaps

The second of these methods we’ll look into today are called the Laplacian Eigenmaps. Unlike LLEs, Laplacian Eigenmap methods define the decoder on the L2 distance between the node embeddings. More specifically,

$$\text{DEC}(\bm{z}_{u}, \bm{z}_{v}) = \| \bm{z}_{u} - \bm{z}_{v} \|_{2}^{2}.$$This decoder punishes node embeddings which are far apart. Next, the loss function is given by the product of the decoder and the similarity matrix:

$$\mathcal{L} = \sum_{(u, v) \in \mathcal{D}} \text{DEC}(\bm{z}_{u}, \bm{z}_{v}) \cdot \bm{S}[u, v].$$The similarity matrix is defined as the normalised Laplacian matrix. To create this normalised Laplacian matrix, first you need to create an $\epsilon$-neighbourhood for each node or find the nodes k nearest neighbours. With the neighbourhood found, next the Laplacian matrix is divided by weights signifying the distance between the nodes. There are two common weighting strategies used to find our weight matrix $W$. First is by using a heat kernel. Second simply assigns the weight of 1 if the nodes are connected, otherwise, the weight is assigned the value 0. Each have their own set of advantages and disadvantages. More details of this process can be found here.

Using this weighting matrix, we can construct the Laplacian $L$:

$$L = D - W,$$where D is a diagonal degree matrix with $D_{ii} = \sum_{j} w_{ij}$.

Now that we have constructed our normalised Laplacian. The next step is to solve the generalised eigenvalue problem.

The optimal solution to minimise the loss is given by the eigenvectors with d smallest non-zero eigenvalues.

Inner Product Methods

The second group of methods are called the inner product methods. These use the assumption that the similarity between two nodes is proportional to their dot product.

$$\text{DEC}(\bm{z}_{u}, \bm{z}_{v}) = \bm{z}_{u}^{T} \bm{z}_{v}.$$Methods such as Graph Factorisation (GF), GraRep, and HOPE used this decoder. This type of decoder is often applied to minimise the mean squared error loss between the decoder and the chosen similarity matrix.

$$\mathcal{L} = \sum_{(u, v) \in \mathcal{D}} \| \text{DEC}(\bm{z}_{u}, \bm{z}_{v}) - \bm{S}[u, v] \|_{2}^{2}.$$Some methods defined the adjacency matrix as the similarity matrix (GF) while other variants used powers of the adjacency matrix as the similarity matrix. In practice, there is no default strategy to go about choosing the similarity matrix and many experts have used different similarity matrices with goals of optimising different problems. We’ll delve deeper into some of these methods in the next sections.

Graph Factorisation

As mention in the last paragraph, the GF factorisation approach defines its similarity matrix as the adjacency matrix. To approximate this adjacency matrix, GF used two matrices $U, V \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}$, where each row of $U$ and $V$ corresponds to a low-dimensional embedding of a node in the graph. The goal of the factorisation is to minimise the difference between the product $U \times V^{T}$. This gives the following loss function:

$$\min_{U,V} f(U,V) = \min_{U,V} \frac{1}{2}\sum_{(i,j) \in E} (A_{ij} - U_{i}V^{T}_{j})^{2} + \lambda (\| U_{i}\|^{2} + \| V_{j}\|^{2}).$$The $\lambda$ term acts as a regularisation to prevent overfitting. This optimisation problem is solved using stochastic gradient descent (SGD). SGD is an optimisation process that involves iterating over the edges in the graph and updating the embedding vectors $U_{i}$ and $V_{j}$ to minimize the error between the actual adjacency value $A_{ij}$ and our reconstruction. It requires differentiating wrt to the edge from node i to j to give:

$$\frac{\delta f}{\delta U_{i, j}} = - (A_{i,j} - U_{i}V^{T}_{j})V_{j} - \lambda U_{i}.$$Using the SGD formula, this gradient is inserted below:

$$U_{i} \leftarrow U_{i} - \mu \frac{\delta f}{\delta U_{i}},$$where $\mu$ denotes the step size. This process is iterated till the Frobius norm between the matrix produced in each iteration is less than the stopping criterion.

The initial reason for two different matrices $U$ and $V$ was to help the matrix generalise to a wide range of different graphs (directed, undirected, weighted, etc.). Note that in the scenario the graph is undirected the adjacency matrix is symmetric so $U\approx V$.

More details can be found by Ahmed and his team here.

GraRep

Unlike GF, GraRep uses a different similarity matrix. GraRep starts by using a row normalised variant of the adjacent matrix. To create this matrix, it defines the probability transition matrix $P$ as $P = D^{-1}A$, where A is the adjacency matrix and D is the degree matrix. A degree matrix is a diagonal matrix where the ith row’s non-zero diagonal element corresponds to the degree of the ith node. This matrix $P$ is not our similarity matrix however it’s used in the calculation of our similarity matrix.

Next we use the concatenation of k adjacency matrices, $P^{k} = P....P$. We’ll denote $P^{k}_{w, c}$ to correspond to the probability of transitioning from vertex $w$ to vertex $c$ in the kth step. In other literature this transition probability is written as $p_{k}(c|w) = P^{k} _{w,c}$.

This transition matrix is used to create our objective function. This gives:

$$L_{k}(w,c) = P^{k}_{w,c} \cdot \log \sigma(w\cdot c) + \frac{\lambda}{N} \sum_{w'} P^{k}_{w', c} \cdot \log \sigma(-w' \cdot c).$$The derivation and reasonings behind this loss function will not be covered today but it can be found here. To minimise this loss we differentiate this loss function wrt $w\cdot c$ and equate to zero. This tells us that the best parameters for $w\cdot c$ are:

$$w\cdot c = \log(\frac{P^{k}_{w,c}}{\sum_{w'}P ^{k}_{w',c}}) - \log(\beta),$$where $\beta = \lambda / N$. Consequently, if we were to find a lower dimensional representation for our similarity matrix $S$ of dimension d (denoted as $S_{d}$), we would need to find a factorisation $W$ and $C$ of $S$ where

$$S_{i,j}^{k} = W^{k}_{i} \cdot C _{j}^{k} = \log \left( \frac{P_{i,j}^{k}}{\sum_{t} P_{t,j}^{k}} \right) - \log (\beta).$$To further improve stability of this method, the negative entries within matrix $S$ are assigned the value 0.

Now that we have our similarity matrix, we can next find our low dimensional representation using SVD.

$$S^{k} = U^{k} \textstyle \sum^{k}_{d} V^{k}.$$Using the d largest singular values of $S$, we can approximate $S^{k} \approx S^{k}_{d} = U^{k}_{d} \sum^{k}_{d} V^{k} _{d}$ where $\sum^{k}_{d}$ corresponds to the first diagonal matrix composed of the top d singular values and $U^{k}_{d}$ and $V^{k} _{d}$ correspond to the first d eigenvectors of $S S^{T}$.

Constructing $S$ as a function of $W$ and $C$ will minimise our loss function above.

$$S^{k} \approx S^{k} = W^{k}_{d}C^{k}_{d}$$$$W^{k} = U^{k}_{d}( \textstyle \sum_{d}^k) ^{\frac{1}{2}}, \quad C^{k} = ( \textstyle \sum _{d}^{k}) ^{\frac{1}{2}}V^{k^{T}}_{d}$$This matrix $W^{k}$ gives our d-dimensional representations of the data which captures the k-step global structural information.

The authors mentioned alternative approaches to SVD could be used for the dimensionality reduction but had yet to be investigated. These include incremental SVD, independent component analysis, and deep neural networks.

Limitations of Shallow Embedding Methods

Before concluding we’ll briefly mention some of the important limitations of shallow embeddings methods.

- First, the parameters between the nodes are not shared. Parameter sharing can greatly improve efficiency and can act as a form of regularisation.

- Shallow embeddings do not leverage node features in the encoder process.

- Shallow embeddings are transductive. This means that methods are only able to generate embeddings for nodes that they have trained on.

Conclusion

Today’s article covered some of the methods used within the graph factorisation for shallow embedding methods. We looked at LLEs, Laplacian Eigenmaps, GF, and GraRep and briefly covered the maths behind their formulation.

Appendix:

A) Laplacian Matrices: A Laplacian matrix is simply a matrix representation of a graph. They have many different definitions and properties depending on the graph. For simple graphs the Laplacian matrix $L$ is also defined as $L = D - A$, where D is the degree matrix and A is the adjacency matrix of the graph. For Laplacian matrix $L$ with eigenvalues $\lambda_{0} \leq \lambda_{1} \ldots \leq \lambda_{n-1}$. Some of the properties of Laplacian matrices $L$ are:

- L is symmetric.

- L is positive semi-definite ($\lambda_{i} \geq 0 \forall i).

- The second smallest eigenvalue is referred to as the algebraic connectivity. It’s used to identify clusters in a graph. In general the smaller eigenvalues capture the large-scale global structure.

- Row and columns sums of L are 0.

- For any Laplacian matrix, there will always exist one eigenvalue with the value 0.

- The number of zero eigenvalues for L is the same as the number of connected components of the graph.

B) The Standard Eigenvalue Problem: Given a square matrix $A$, the goal is to find non-zero vectors $x$ and scalars $\lambda$ such that

$$Ax = \lambda x$$Vectors which satisfy this problem are called eigenvectors and the scalars are called $eigenvalues$.

The Generalised Eigenvalue Problem: Given square matrices $A$ and $B$, the goal is to find non-zero vectors $x$ and scalars $\lambda$ that satisfy:

$$Ax = \lambda B x$$These type of problems appear when the properties of the matrices $A$ and $B$ are required for solving another engineering or mathematical problem.

References:

William, W.L. (2022). Graph Representation Learning. Springer Nature.

Kumar, S. (2023). Shallow Embedding Models for Homogeneous Graphs. [online] Reachsumit.com. Available at: https://blog.reachsumit.com/posts/2023/05/shallow-homogeneous-graphs-rep/ [Accessed 20 Aug. 2024].

Roweis, S.T. (2000). Nonlinear Dimensionality Reduction by Locally Linear Embedding. Science, 290(5500), pp.2323–2326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5500.2323.

Belkin, M. and Niyogi, P. (2003). Laplacian Eigenmaps for Dimensionality Reduction and Data Representation. Neural Computation, [online] 15(6), pp.1373–1396. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/089976603321780317.

Google, A., Shervashidze, N., Bangalore, M., Google, V. and Smola, A. (n.d.). Distributed Large-scale Natural Graph Factorization * Shravan Narayanamurthy. [online] Available at: https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//pubs/archive/40839.pdf [Accessed 20 Aug. 2024].

Cao, S., Lu, W. and Xu, Q. (2015). GraRep. Proceedings of the 24th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/2806416.2806512.