Image by Will Turner

In this article, we will cover what containerisation means and we look at Docker, a containerisation platform. Furthermore, we will cover the key commands and concepts needed to create your own containers in docker.

Image by Will Turner

In this article, we will cover what containerisation means and we look at Docker, a containerisation platform. Furthermore, we will cover the key commands and concepts needed to create your own containers in docker.

What is Docker?

Docker is an open-source software platform that assists the deployment of applications. It does this by creating standardised units called containers which are isolated environments containing the application code, runtime, libraries, and any dependencies. These containers are a type of virtual machine that has an OS but does not simulate the entire computer. It is like a sandboxed environment.

The goal of containers is to provide portability, meaning you can run the same container on any computer environment. This even works with environments with a different OS and hardware.

Another advantage of these containers is their consistency. Since they are decoupled from the environment in which they are run, they are guaranteed to run the same, regardless of where they are deployed.

Containers vs Virtual Machines

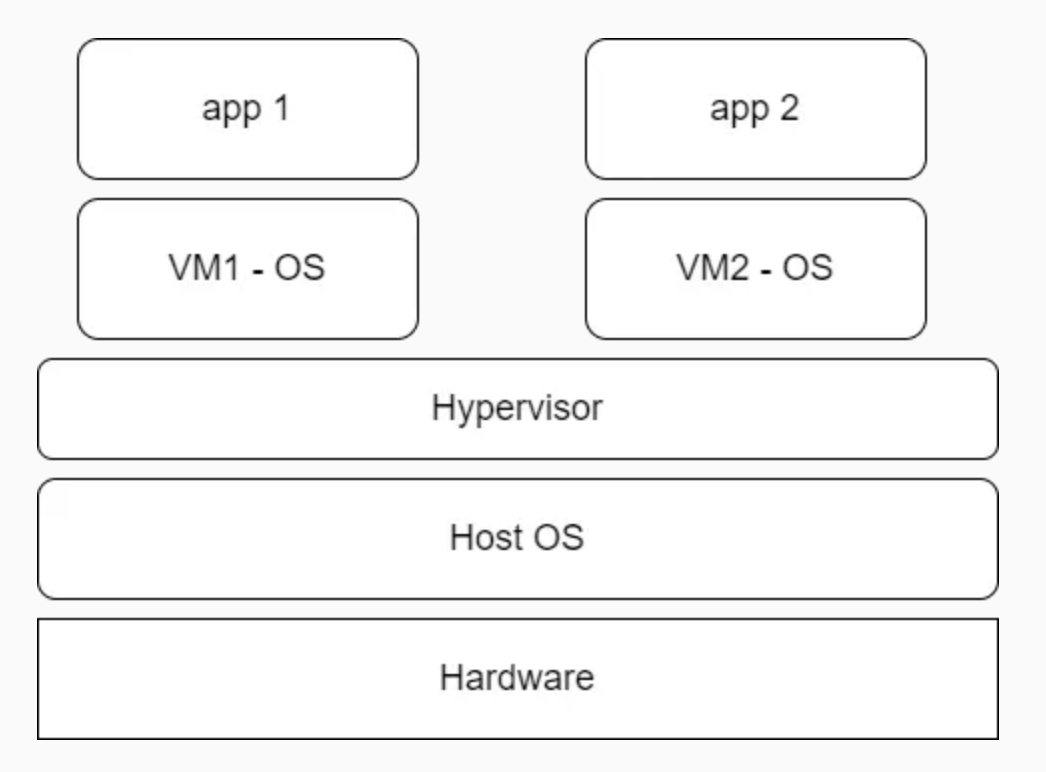

A virtual machine (VM) [1] is another way of creating a virtual environment. A VM is a computer that lives inside a host machine and they are created by virtualising [appendix 1] the host machine’s underlying hardware and OS. The hardware is virtualised and then a portion of the hardware is used to run the VM.

Figure 1. Virtual Machines. Source found at: https://endjin.com/blog/2022/01/introduction-to-containers-and-docker

What sits between the host OS and the VM is a hypervisor layer. This is a piece of software that virtualises the host’s hardware and acts as the broker which manages the resources such as CPU, memory, and OS such that multiple different VMs can be run on the same hardware simultaneously. It is important to mention each VM may require different amounts of resources and the hypervisor is used to manage these resources.

The main disadvantage of a VM is its duplication. For each VM, a new OS is initialised which requires CPU, memory, and storage to run to create machine level isolation between each VM. However, this makes the VM slower to boot up and more inefficient with its resource management.

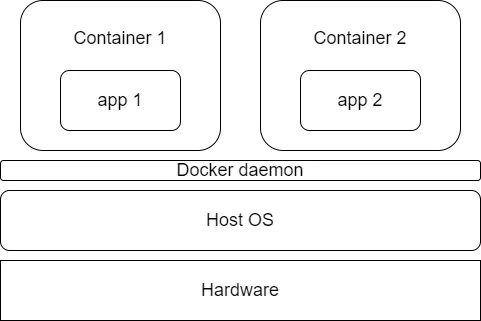

Containers aim to solve this issue. The containers virtualise only the application and its dependencies rather than the whole OS. As a result, each container doesn’t need to have its own OS which makes them more lightweight than VMs.

Containers are best thought of as processes on the host system with isolated environments.

Figure 2. Containers. Source found at: https://endjin.com/blog/2022/01/introduction-to-containers-and-docker

Rather than using a hypervisor layer, the docker containers use a Docker daemon which acts as a broker between the host OS and containers. Docker Daemon chooses to use the host’s kernel directly to share the host OS with all containers. This process is more efficient than VMs and allows for rapid deployment.

Docker Images

Now that we know what docker containers are, you may wonder where the containers get their files and configurations. This is when docker images step in. These images are standalone packages which include all the files, binaries, libraries, and configs required to start running a container and at runtime, the images are converted to containers.

Here are key principal’s of Docker images [2]:

- Images are Immutable. This means that Docker images cannot be altered after they are created. You can think of an image as a snapshot of a file system at a particular point in time. If you want to make changes (like installing new software or modifying files), you cannot alter the existing image directly. Instead, you can create a new image with those changes.

- Container Images are composed of layers where each layer represents a set of file system changes. These layers stack on top of each other and each command in the Dockerfile (we’ll cover this later) creates a new layer in the image. For example, in a project you have a base layer consisting of installing python. The subsequent layer may copy the application code to the container and the final layer may install additional libraries from the requirements.txt.

Many docker images can be found at the Docker Hub website. Docker hub contains thousands of trusted images such as pytorch, tensorflow, postgres, neo4j, python, wordpress images and many more.

In case their is still any confusion between what a Docker images and docker container is. The Docker image provides the blueprints of an application while a docker container is the running instance of that Docker image.

During your own projects, the base images may be insufficient. In this situation a Dockerfile is needed. A Dockerfile allows the user to create highly customisable environments tailored to the application’s needs. It allows the user to build an environment by specifying the OS, configuration files, environment variables, and more.

Lets create a Dockerfile which uses the default python image which adds the current application code to the container and installs the requirements.txt.

# Base layer: Start with an official Python image from Docker Hub

FROM python:3.9-slim

# Set the working directory in the container

WORKDIR /app

# Copy only the requirements.txt file first to leverage Docker layer caching for dependencies

COPY requirements.txt .

# Install the necessary libraries specified in requirements.txt

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt

# Copy the rest of the application code into the container

COPY . .

# Specify the command to run the application

CMD ["python", "app.py"]

- FROM: specifies the base image to be used. The remaining commands are then used to provide additional functionality to the base image. In general, this new image is called a child image.

- WORKDIR: sets the current the app directory as the working directory for the container.

- COPY: copies the requirements.txt file from the current directory to the current directory in the container.

- RUN: runs a set of instructions once the container is called to be built.

- CMD: specifies a default command to be run when the container is started.

Using a Dockerfile allows the user to create a consistent environment that behaves the same on any machine in Docker.

To create a Docker Image from a DockerFile run the command:

docker build -t my_custom_image .

- -t <my_custom_image>: Tags the image with the name my_custom_image.

- .: specifies the build context. This enables Docker to look through the current directory for a Dockerfile.

Now that the Docker Image has been made, the next step is to create the container.

docker run -d --name my_app_container -p 3000:3000 my_custom_image

- -d: runs the container in detached mode, allowing the container to run in the background.

- –name: provides a name for the container. Without this, docker will create a default name for the container using a string of random characters.

- -p: maps your device’s port 3000 to the container’s port 3000.

- my_custom_image: specifies the image to be used to create the container.

To check the container is running:

docker ps

This will display a list of running containers.

There are a few other commands that are useful to know.

To display the logs of the running container run:

docker logs my_app_container

To open the shell of the running container:

docker exec -it my_app_container /bin/bash

- -it: -i (the interactive flag) keeps the session open to accept inputs. -t (the TTY flag) allocates a pseudo-TTY, allowing the the terminal to be interactve.

- /bin/bash: specifies a command to be run inside the container, in our case /bin/bash opens a bash shell.

To stop the container:

docker stop my_app_container

To remove the container:

docker rm my_app_container

Docker Volumes

The final concept we will cover are volumes. Whenever a docker container is stopped all the information from that container is deleted. Volumes are a solution to this issue by providing a location to store the data outside the container on the host’s system (typically at ‘var/lib/docker/volume’). Now when the container is stopped, the information will not be deleted.

Some of the situations where this feature comes in handy includes:

- database storage.

- application data.

- data backups.

There are a few different types of volumes within Docker.

Anonymous Volumes. These are volumes created by Docker without specifying a name. They are typically created by Docker to store data that is only required during the lifetime of the docker container and are removed when the container is terminated.

docker run -v /app/data my_image

- docker run: starts a new container from an image (my_image).

- -v: specifies a volume to be mounted into the container.

- /app/data: is used as a shorthand for an anonymous volume. Without specifying a path on the host system docker will mount the volume /app/data directory in the container.

Names Volumes. As the name implies, these volumes are created with a specific name and are used when a user wants the data to persists beyond the lifetime of the container. Since these are managed independently of the container, they are not deleted once the container is removed.

To create a volume run

docker volume create my_volume

docker run -v my_volume:/app/data my_image

- -v: mounts a volume into the container. In our case, it maps the volume we made called my_volume to the /app/data directory in the container.

Host Volumes (Bind Mounts). This class of volumes are not traditional volumes, rather they are grouped with volumes. Bind mounts directly mount a directory from the host system into the container. These volumes are used when we need them.

docker run -v /path/on/host:/app/data my_image

Some of the other important docker volume commands include:

To list the docker volumes:

docker volume ls

To inspect a volume:

docker volume inspect my_volume

Conclusion

In this article, we covered the basic of docker’s containerisation design. Additionally, we discussed how to create docker images and volumes.

Appendix

- Virtualisation: To virtualise something means to create a virtual version of it. This includes creating virtual version of the server, storage, and OS. Rather than having 1 piece of hardware for each virtualisation, one physical resource can act as multiple independent resources.

- Kernel: A kernel [3] is a mediator between an application software and the hardware components. It is responsible for managing the computer’s resources such as CPU, RAM, storage, etc and it dictates when various resources are utilised across applications. Kernels manage all the aspects of a process by scheduling when they are to run and cleaning them up.

References

- Mooney, L. (2022). Introduction to Containers and Docker | endjin. [online] endjin.com. Available at: https://endjin.com/blog/2022/01/introduction-to-containers-and-docker.

- Docker Documentation. (2024). What is an image? [online] Available at: https://docs.docker.com/get-started/docker-concepts/the-basics/what-is-an-image/.

- Team, H. (2024). What is a Kernel & How Does it Work? [online] Hostwinds Blog. Available at: https://www.hostwinds.com/blog/what-is-a-kernel-and-how-does-it-work# [Accessed 11 Nov. 2024].