[Image by Justin Lim]

[Image by Justin Lim]

Introduction

This article will delve into diffusion models, a group of latent variable (see definitions) generative models with applications in image generation, audio synthesis, and denoising. More specifically, this article will mostly focus on the derivations and the ideas behind diffusion models, with a heavy enthuses on the ideas introduced in Ho et al. in his Denoising Diffusion Probabilisitic Models paper (DDPMs). The applications of these models will not be covered today.

Introduction to probabilistic modelling

Before delving into diffusion models, it’s best to briefly cover some of the common issues in probabilistic modelling. As explained by J.Sohl-Dickstein et al., in probabilistic modelling, there has always been the trade-off between two conflicting objectives. These objectives are tractability and flexibility.

Tractable models are those that fit easily to data and that can be analytically evaluated. However, these models often lack the complexity required to model complex datasets.

On the contrary, flexible models have the ability to model any arbitrary data. For example, any distribution of data $\mathcal{X}$ can be represented by a scoring function $\phi(\bm{x}) \geq 0$, $\forall x \in \mathcal{X}$. To construct a probabilistic distribution from this function, we need to divide by a normalizing constant $C$, where $C = \int \phi(x) \ \delta x$, giving us $p(x) = \phi(x) / C$. The challenge with this method arises from the intractability of this normalisation term. We will explore this limitation further later in this article.

Diffusion models sit in the middle between these two objectives. They provide extreme flexibility while remaining tractable. To achieve this a generative Markov chain is used. This chain iteratively converts a simple known distribution (often a Gaussian distribution) to the target distribution. The model learns in each step by estimating the small perturbations in the sample rather than estimating the target function from a single non-analytically-normalisable potential function.

This idea stems from the fact that a diffusion process exists for any smooth target function. Consequently, a diffusion process can model distributions of arbitrary form.

What are diffusion models?

Diffusion models are broken down into 2 key processes. The forward process and the reverse process. The forward process gradually adds Gaussian noise to an image, slowly corrupting the image. On the other hand, the reverse process takes this corrupted image and iteratively tries to remove the noise from the corrupted image. In the process of removing the noise, a function (often a neural network) is trained to remove this noise. After a long training process, this new function will have the ability to generate samples from random noise.

Diffusion models are inspired by two key processes. The forward and backward processes in diffusion models are rooted in the concept of diffusion in physics, where particles naturally move from areas of high concentration to low concentration. This is where the term “diffusion” in the model’s name comes from.

The second, slightly more complex, inspiration comes from Sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) methods. SMC methods are simulation-based techniques used to approximate the posterior distribution, which is particularly useful for modelling dynamic systems where states evolve over time.

These models have been shown to be competitive and even surpass the performance GANs and VAEs architectures in many high quality image generation tasks. They’re also the backbone architecture used by many of the modern day image generation models such as OpenAI Sora, Stable Diffusion, DALL-E 2, Imagen, Latent Diffusion Models, and many more.

Forward Process

The forward process starts with starting point $\bm{x}_{0} \sim q$, where $\bm{x}_{0}$ is an uncorrupted image and $q$ is the marginal probability distribution. We iteratively add Gaussian noise to the sample image over T steps producing a set of increasing corrupted samples $\{\bm{x}_{1}, \bm{x}_{2}, ... \bm{x}_{T}\}$, with each of these step sizes controlled by a variance scheduler parameter $\{ \beta_{t} \in (0,1)\}^{T}_{t=1}$ . Under this assumption, the marginal probability distribution $q$ given the corrupted image $\bm{x}_{t-1}$ can be modelled with a Gaussian distribution:

$$ q(\bm{x}_{t}|\bm{x}_{t-1}) = \mathcal{N}(\bm{x}_{t}; \sqrt{1 - \beta{t}}\bm{x}_{t-1}, \beta_{t}\bm{I}).$$

Figure 1. An example forward diffusion process. Source: Nichol & Dhariwal

The iterative nature of progressively adding noise to the images is inspired by Markovian processes where the subsequent state of an event $\bm{x}_{t+1}$ is only dependent on the current state of the event $\bm{x}_{t}$. This can be shown of mathematically with the probability of getting the sequence of images $\bm{x}_{1}, ..., \bm{x}_{T}$ given start image $\bm{x}_{0}$ is:

$$p(\bm{x}_{1}, ..., \bm{x}_{T} | \bm{x}_{0}) = \prod _{t=0}^{T} p(\bm{x}_{t} | \bm{x}_{t-1}).$$For any given time step t, in order to avoid having to iteratively calculate the previous samples from $\bm{x}_{0}$, to $\bm{x}_{t-1}$ to apply the noise to the sample at step $t$, we can instead use the following reparameterization trick. First let $\alpha_{t} = 1 - \beta_{t}$ and $\overline{\alpha} = \prod_{i=1}^{t}\alpha_{i}$. If we define $\bm{\epsilon}_{t-1}$, … to be random variables from a normal distribution $\mathcal{N}(\bm{0}, \bm{I})$, then we can write $\bm{x}_{t}$ as a function of $\bm{x}_{0}$:

$$\begin{aligned}\bm{x}_t &= \sqrt{\alpha_t} \bm{x}_{t-1} + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_t} \bm{\epsilon}_{t-1} \\ &= \sqrt{\alpha_t}(\sqrt{\alpha_{t-1}}\bm{x}_{t-2} + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_{t-1} }\bm{\epsilon}_{t-2}) + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_t} \bm{\epsilon}_{t-1} \\ &= \sqrt{\alpha_t \alpha_{t-1}}\bm{x}_{t-2} + \sqrt{\alpha_t (1 - \alpha_{t-1})}\bm{\epsilon}_{t-2} + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_t} \bm{\epsilon}_{t-1} \\ &= \sqrt{\alpha_t \alpha_{t-1}} \bm{x}_{t-2} + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_t \alpha_{t-1}} \bm{\bar{\epsilon}}_{t-2} \\ &= \cdots \\ &= \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \bm{x}_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \bm{\epsilon}\end{aligned}$$where $\bm{\epsilon}$ merges the $n$ gaussian distributions and the third to fourth line uses the fact that if $X \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^{2}_{1} \bm{I})$ and $Y \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^{2}_{2} \bm{I})$, then $X + Y \sim \mathcal{N}(0, (\sigma^{2}_{1} + \sigma^{2}_{2}) \bm{I})$.

Using this formula, we now have a tractable way to apply the noise for the sample at any time step.

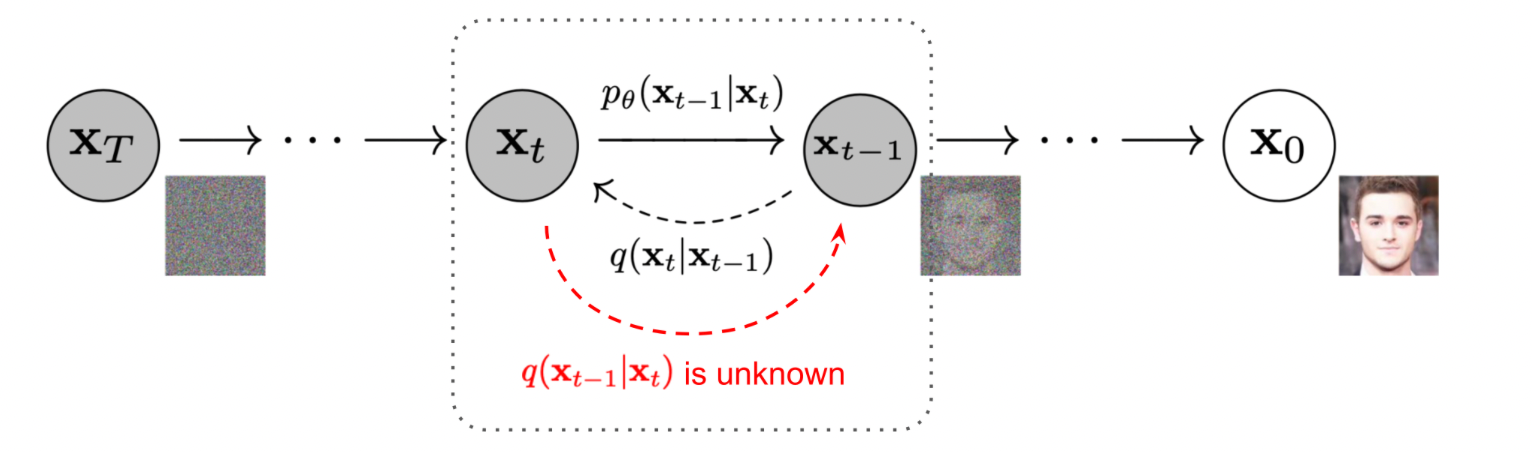

Backward Diffusion Process

Now that we know how to add noise to a sample, we need to know how to remove noise from a sample. This process is called the backward diffusion process. The goal of the backward process is to learn the conditional probability distribution of $q(\bm{x}_{t-1}| \bm{x}_{t})$. However, learning $q(\bm{x}_{t-1}| \bm{x}_{t})$ turns out to be intractable (see the definitions section) and needs to be approximated. To show why $q(\bm{x}_{t-1}| \bm{x}_{t})$ is intractable we’ll start by writing the backward process using Bayes theorem:

$$q(\bm{x}_{t-1}| \bm{x}_{t}) = \frac{q(\bm{x}_{t}| \bm{x}_{t-1}) q(\bm{x}_{t-1})}{q(\bm{x}_{t})} = \frac{q(\bm{x}_{t}| \bm{x}_{t-1}) q(\bm{x}_{t-1})}{\int q(\bm{x}_{t}|\bm{x}_{t-1})q(\bm{x}_{t-1}) d\bm{x}_{t-1}}.$$Computing the marginal distribution $q(\bm{x}_{t})$ requires integrating over a high dimensional space which is generally intractable and the distribution $q(\bm{x}_{t})$ is often complex and doesn’t have a closed form solution.

Consequently, we need to learn a model $p_{\theta}$ to approximate the conditional distribution $q(\bm{x}_{t-1}| \bm{x}_{t})$ to reverse the noise. This model will take two arguments $\bm{x}_{t}$ and $t$. $\theta$ corresponds to the model’s parameters the model will learn.

W .Feller proved in his paper on the theory of stochastic processes that for Gaussian and binomial diffusion processes (with small step sizes $\beta$), the reversal of these diffusion process also has an identical form to the forward process. This forms the foundation of our theory here. If the forward process uses a small enough step sizes $\beta_{t}$, then the reverse process $q(\bm{x}_{t-1} \| x_{t})$ also follows a Gaussian distribution. Consequently, we only need to create a model to find the parameters $\mu_{\theta}(x_{T}, t)$ and $\sum_{\theta}(x_{t}, t))$ to estimate the backward diffusion process.

$$p_{\theta}(\bm(x)_{t-1}|\bm{x}_{t}) = \mathcal{N}(\bm{x}_{t-1}|\mu_{\theta}(x_{t}, t), \sum_{\theta}(x_{t},t)).$$There are many different models we could choose to estimate these parameters. In J, Sohl-Dickstein first application of diffusion models, he used a MultiLayer Perceptron, but more of the modern methods tend to use a Neural Network inspired by U-Net. Using either of these models, the next steps are finding the correct parameters of our NN which minimise the divergence of $p_{\theta}(\bm{x}_{0})$ from distribution $q(\bm{x}_{0})$. This is done by borrowing some of the ideas around Variational Inference (VI) from Bayesian Statistics.

Figure 2. The reverse diffusion process. Source: Ho et al. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2006.11239

Variational Inference:

In short, VI revolves around a family of techniques used for approximating intractable integrals arising in Bayesian statistics. The goal of variational inference is to find a way to approximate the posterior probability of unobserved variables by using the Evidence lower bound (ELBO). The ELBO provides us with a lower bound on the loss of our approximate distribution. This lower bound is often known as the variational free energy. We won’t delve any more into this lower bound here but more details can be found here. The ELBO inequality applied to our situation gives:

$$\ln p_{\theta}(\bm{x}_{0}) \geq \mathbb{E}_{\bm{x}_{1:T} \sim q(\cdot | \bm{x}_{0})} \left[ \ln p_{\theta} (\bm{x}_{0:T}) - \ln q(\bm{x}_{1:T} | \bm{x}_{0}) \right] .$$Taking expectation wrt to $x_{0}$ gives:

$$\mathbb{E}_{\bm{x}_{0} \sim q} \left[ \ln p_{\theta} (\bm{x}_{0}) \right] \geq \mathbb{E}_{\bm{x}_{0:T} \sim q(\cdot \mid \bm{x}_{0})} \left[ \ln p_{\theta} (\bm{x}_{0:T}) - \ln q(\bm{x}_{1:T} \| \bm{x}_{0}) \right]$$Since the term on the left is fixed, we now have an upper bound. Consequently, we want to maximise the terms on the right by minimising the divergence of $\ln p_{\theta} (\bm{x}_{0:T}) $ from $q(\bm{x}_{1:T} | \bm{x}_{0})$. Using this formula, a loss function can be created by multiplying the formula above by negative 1.

$$L(\theta) = -\mathbb{E}_{\bm{x}_{0:T} \sim q} \left[ \ln p_{\theta} (\bm{x}_{0:T}) - q(\bm{x}_{1:T} | \bm{x}_{0}) \right].$$Minimising this loss function is equivalent to minimising the divergence between the two functions. This can be re-written to:

$$L(\theta) = \sum_{t=1}^{T} \mathbb{E}_{\bm{x}_{t}, \bm{x}_{t-1} \sim q} \left[ -\ln p{\theta} (\bm{x}_{t-1} | \bm{x}_{t}) \right] + \mathbb{E} \left[ D_{\text{KL}} (q(\bm{x}_{T} | \bm{x}_{0}) | p_{\theta} (\bm{x}_{T})) \right].$$Since the term $p_{\theta} (\bm{x}_{T})$ is completely independent of any parameters, this KL divergence term can be ignored. This gives the simpler loss function to be minimised:

$$L(\theta) = \sum_{t=1}^{T} L_{t} \ \text{ where } L_{t} = \mathbb{E}_{\bm{x}_{t-1}, \bm{x}_{t} \sim q} \left[ -\ln p_{\theta} (\bm{x}_{t-1} | \bm{x}_{t}) \right]. $$Some form of the gradient descent algorithm will be applied to this function in hopes to minimise the loss (and consequently be able to identify the noise). Many lines of code are skipped in this proof (for my sanity), however, I’d recommend reading this GitHub post which covers the proofs behind the whole process.

Much of this section follows the work from here.

Back to the backward diffusion step

Now that we know what we are trying to minimise, the next step is determining how we’re going to do this.

Deriving a formula for $q(\bm{x}_{t-1} | \bm{x}_{t})$ is impossible because this distribution relies on the value $\bm{x} _{0}$ which is not available during inference. If you think about this intuitively, it will be incredibly difficult to predict the noise of an image without knowing the end image with no noise. However, if we were to condition the distribution on $\bm{x}_{0}$, we will now have a tractable way to predict the noise. Most the proof for the formulas below will be skipped for now but can be found here.

$$q(\bm{x}_{t-1}|\bm{x}_{t}, \bm{x}_{0}) = q(\bm{x}_{t}|\bm{x}_{t-1}, \bm{x}_{0}) \frac{q(\bm{x}_{t-1} | \bm{x}_{0})}{q(\bm{x}_{t} | \bm{x}_{0}) }$$Since each of these distributions on the left can be expressed as a normal distribution, they can be multiplied together creating another normal distribution with parameters $\tilde{\bm{\mu}}_{t}(\bm{x}_{t}, \bm{x}_{0})$ and $\tilde{\beta_{t}}$.

$$\begin{align*} q(\bm{x}_{t-1} | \mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0) &= \mathcal{N}\left(\bm{x}_{t-1}; \tilde{\bm{\mu}}_t(\mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0), \tilde{\beta}_t \mathbf{I}\right) \\ \tilde{\beta}_t &= \frac{1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t-1}}{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \cdot \beta_t \\ \tilde{\bm{\mu}}_t(\mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{x}_0) &= \frac{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t-1}} \beta_t}{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_0 + \frac{\sqrt{\alpha_t}(1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t-1})}{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_t \end{align*}$$The only issue with conditioning on $\bm{x}_{0}$ is that it defeats the process of generating samples from random noise. When you generate samples in practice you won’t have the clean sample $\bm{x}_{0}$ . Consequently, we can’t use the true sample of $\bm{x}_{0}$, however it can be estimated. Using the simplified formula from the forward diffusion process we can write $\bm{x}_{0}$ as a function of $\bm{x}_{t}$.

$$\begin{aligned} \bm{x}_{t} &= \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \bm{x}_{0} + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \bm{\epsilon} \\ \bm{x}_{0} &= \frac{\bm{x}_{t} - \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \bm{\epsilon}}{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t}}. \end{aligned}$$Substituting this estimation of $\bm{x}_{0}$ into the function $\mu$ gives:

$$\tilde{\mu}_t(\mathbf{x}_t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha_t}} \left( \mathbf{x}_t - \frac{\beta_t}{\sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t}} \bm{\epsilon} \right).$$Next we will write $\bm{\epsilon}$ as a function of $\mathbf{x}_{t}$ and $t$:

$$\tilde{\mu}_{\theta}(\mathbf{x}_t, t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha_t}} \left( \mathbf{x}_t - \frac{\beta_t}{\sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t}} \epsilon_{\theta}(\mathbf{x}_t, t) \right).$$Substituting these terms into our loss function from earlier. We get:

$$\begin{aligned}L_t &= \mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{x}_0, t, \epsilon} \left[ \frac{1}{2 \|\Sigma_{\theta}(\mathbf{x}_t, t)\|_2^2} \|\tilde{\mu}_t - \mu_{\theta}(\mathbf{x}_t, t)\|_2^2 \right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{x}_0, t, \epsilon} \left[ \frac{\beta_t^2}{2 \alpha_t (1 - \bar{\alpha}_t) \|\Sigma_{\theta}\|_2^2} \|\epsilon_t - \epsilon_{\theta}(\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_t} \mathbf{x}_0 + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_t} \epsilon, t)\|_2^2 \right]\end{aligned}$$With these substitutions and rearrangements, we have simplified the problem. Now we only need to estimate the variance term ($\Sigma_{\theta}$) and the noise term ($\bm{\epsilon}$) term for every timestep $t \in \left[1, T\right]$.

These loss functions was further simplified in the paper by Ho et al., where he removed the weighting term giving the final loss function:

$$L_{t}^{\text{simple}} = \mathbb{E}_{x_{0},t,\epsilon} \left[ \left| \epsilon - \epsilon_{\theta} \left( \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}t} \bm{x}_{0} + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t}} \bm{\epsilon}, t \right) \right|^{2} \right].$$Note that of the math in this section follows the website here.

DDPM Specifics

During testing Ho et al. found that when they tried estimating the variance term $\beta_{t}$, model training became unstable and model sample quality deteriorated. Ho et al. observed better performance when $\sum_{\theta} (\bm{x}_{t}, t) = \sigma^{2}_{t} \bm{I}$ and $ \sigma^{2} _{t}$ were fixed to the hyper-parameter $\beta_{t}$.

To ensure the reverse process could be modelled as a gaussian distribution Ho et al. decided to use a linearly increasing step size $\beta_{t}$ from $\beta_{0} = 10^{-4}$ to $\beta_{T} = 0.02$ with $T$ chosen to be 1000 steps. It’s worth mentioning many believe these choices of $\beta$ were quite low given the fact that the image pixel values were in the interval $\left[-1, 1\right]$. This parameter was changed on the next iterations of this model.

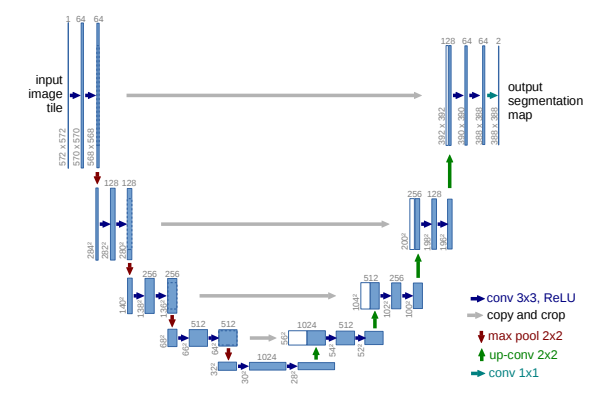

To estimate the noise $\bm{\epsilon}_{t}$ at each timestep $t \in \left[1, T\right]$ a U-Net inspired architecture from Ronneberger et al. was used.

Figure 3. The U-Net Architecture. Source: Ronneberger et al.

However, there were a few key differences to the generic U-Net model.

- Residual Blocks: The first difference were in the type of convolution blocks used. Unlike typical U-Net blocks which do not incorporate skip-connections, Ho et al. added skip-connections to these blocks. Skip connections are often used to help improve gradient flow and avoid the vanishing or exploding gradient problem.

- Attention Mechanisms: Second, self-attention layers were incorporated into the U-Net. Attention mechanism help the model capture long-term relationships.

- Group Normalization: Instead of Batch Normalization, Group Normalization was used to stabilize the training process. In most situations, Batch Normalisation should be used instead of Group Normalisation. However in the setting where the input data is not IID, then group normalisation is preferred. A common example where the data is not IID occurs when the data comes from different classes.

- Sinusoidal Position Embeddings: Finally a sinusoidal position embedding is used to encode the timesteps. This information is then added to the input of every residual block. This of course takes inspiration from the positional encodings used in Transformers.

Conclusion

This article introduced the idea of diffusion models and delved into their mathematical foundation. The diffusion model DDPM was used as an example.

Definitions

Intractability: A problem which can be solved in theory (given large enough but finite resources, and time) but requires too many resources to be useful. These group of problems are known as intractable. On contrary, a problem that can be solved in practice is known as a tractable problem.

Latent Variables: Latent variables are inspired by the latin word “lateo” which means “lie hidden”. These are a class of variables that are not directly observed or measured. They are only inferred through the observed variables. It’s best thinking of these variables as hidden variables.

References:

Sohl-Dickstein, J., Weiss, E., Maheswaranathan, N., Ganguli, S. and Edu, S. (n.d.). Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics. [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1503.03585.

Ho, J., Jain, A. and Abbeel, P. (2020). Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. [online] Available at: c.

Adaloglou, S. K. . N. (2022, September 29). How diffusion models work: the math from scratch | AI Summer. AI Summer. https://theaisummer.com/diffusion-models/

Wikipedia contributors. (2024, July 25). Diffusion model. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_model

Weng, L. (2021, July 11). What are Diffusion Models? Lil’Log. https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2021-07-11-diffusion-models/